10 Uncomfortable Health & Fitness Truths That Will Transform Your Approach to Wellness

- Dr. E

- May 11, 2025

- 19 min read

1. Health is Hard (But the Alternative is Harder): The Crisis of Preventable Disease

The modern healthcare paradox is stark: despite unprecedented medical advances, we face an epidemic of preventable chronic diseases. According to the CDC, 6 in 10 American adults have at least one chronic disease, with 4 in 10 managing the combo pack of two or more (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023).

Heart disease alone kills approximately 695,000 Americans yearly—that's 1 in 5 deaths. For perspective, if diseases were competing for market share, cardiovascular conditions would be the Apple of killing us.

Chronic diseases account for 90% of the nation's $4.1 trillion in annual healthcare expenditures. That's more than $12,500 for every person in America—yet much of this spending treats symptoms rather than addressing root causes.

Why Health is So Darn Hard

Several factors make addressing preventable chronic disease particularly challenging:

Evolutionary mismatch: Our bodies evolved in environments of scarcity and high physical demand—nearly the opposite of our modern world of abundance and convenience. Our ancient ancestors never had to say, "I'll pass on the extra food, I'm watching my calories."

Delayed consequences: The brownie rewards you NOW. The potential diabetes scolds you LATER. Guess which one your brain prioritizes?

Environmental challenges: Try walking anywhere in suburban America without feeling like you're taking your life in your hands.

Psychological barriers: Changing ingrained habits requires overcoming powerful reward pathways that evolved to ensure survival.

Social pressure: That friend who says, "Come on, one beer won't kill you" has never learned basic multiplication. Our social circles can either support health or sabotage it.

The Prevention Paradigm Shift

Research published in the New England Journal of Medicine estimated that 60-70% of premature deaths and two-thirds of the quality-of-life gap in the U.S. could be eliminated through lifestyle modifications addressing tobacco use, poor diet, physical inactivity, and related risk factors (Schroeder, 2007).

The evidence is clear: most chronic diseases are preventable through lifestyle factors, yet our reactive healthcare model waits until these conditions manifest before intervening. By then, managing—rather than curing—becomes the goal, leading to decades of reduced quality of life, increased healthcare costs, and premature death.

Health is hard because it requires consistent effort in a world seemingly designed to undermine it. As the saying goes: The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second-best time is now. The same goes for health habits—though unlike trees, they require daily attention for the rest of your life.

2. Your Genes Aren't Your Destiny: Epigenetics and Lifestyle Impact

"I just have a slow metabolism" and "everyone in my family is overweight" often serve as genetic get-out-of-jail-free cards. But science tells a more empowering story.

The traditional view that your genetic code dictates your destiny has undergone a revolutionary shift. Epigenetics—the study of how behaviors and environment affect how genes work—has dramatically changed our understanding.

The Science Behind Lifestyle Dominance

A landmark study published in the New England Journal of Medicine examined nearly 55,000 people and found that even those with high genetic risk for heart disease could reduce their risk by nearly 50% through lifestyle modifications including regular physical activity, healthy diet, not smoking, and moderate alcohol consumption (Khera et al., 2016).

The Danish Twin Registry studies (some of the largest twin studies in the world) suggest that genetics accounts for only about 20-30% of longevity determination, with the remaining 70-80% attributed to environmental and lifestyle factors (Christensen et al., 2006).

Disease-Specific Evidence

The power of lifestyle over genetic predisposition varies by condition:

Type 2 Diabetes: Once considered highly heritable, intensive lifestyle intervention programs have been shown to reduce diabetes risk by over 58% in high-risk individuals—more effective than medication—according to the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group (Knowler et al., 2002).

Heart Disease: The INTERHEART study examined over 50,000 people across 52 countries and found that modifiable risk factors accounted for over 90% of heart attack risk, regardless of genetic background (Yusuf et al., 2004).

Cancer: The World Cancer Research Fund estimates that about 40% of all cancers are preventable through lifestyle modifications. Even in families with hereditary cancer syndromes, environmental factors significantly influence whether cancer develops.

Alzheimer's Disease: While certain genetic markers like APOE4 increase risk, studies show that cognitive stimulation, physical activity, and diet can significantly delay or prevent onset even in high-risk individuals.

"The old adage "genetics loads the gun, but environment pulls the trigger" has evolved: genes may load the gun, but lifestyle choices can unload it, aim it elsewhere, or transform it completely. You're not stuck with your family's health history—you're writing your own sequel."

3. Your Body Is Designed for Movement (And Punishes You When You Don't Use It)

Our bodies have evolved over millions of years as sophisticated movement systems. Modern conveniences have dramatically reduced our need to move, but our biology remains optimized for it.

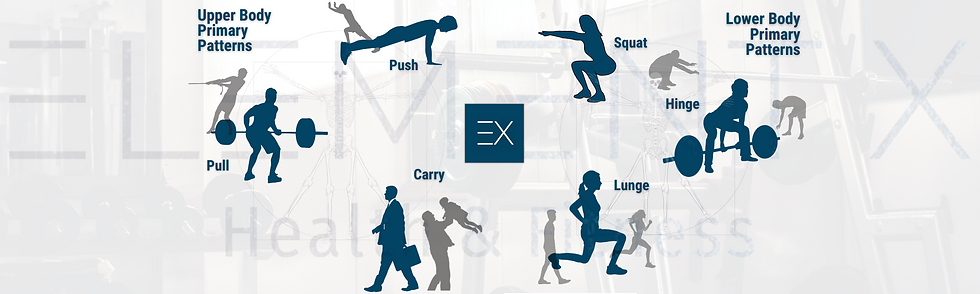

The Six Fundamental Movement Patterns

The human body operates on six fundamental movement patterns essential for functional independence:

Squatting: Essential for toileting, sitting, and rising

Hinging: Proper mechanics for lifting objects

Lunging: Required for walking and navigating stairs

Pushing: Necessary for self-care and daily activities

Pulling: Critical for counterbalancing pushing movements

Carrying: Integrates all other patterns and builds core strength

The Statistical Reality of Sedentary Living

According to the World Health Organization, physical inactivity is the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality, causing an estimated 3.2 million deaths annually (WHO, 2020).

Research in the New England Journal of Medicine tracking over 300,000 individuals found that each hour of sedentary behavior increases mortality risk by approximately 11% (Biswas et al., 2015).

Biological Mechanisms Behind the "Movement Mandate"

Without regular movement, several biological systems deteriorate rapidly:

Muscles: Two weeks of bed rest can result in 5-8% muscle loss in older adults, with strength losses approaching 15-20% (English & Paddon-Jones, 2010).

Heart: Just three weeks of bed rest can decrease cardiovascular fitness (VO2 max) by up to 25% (Convertino, 1997).

Metabolism: Healthy young adults who reduced their step count from 10,000 to 1,500 steps per day for just two weeks experienced a 67% increase in insulin resistance (Krogh-Madsen et al., 2010).

Bones: Without mechanical loading, bone demineralization accelerates. Astronauts in zero gravity can lose 1-2% of bone mineral density per month.

Brain: Regular physical activity was associated with a 20-30% reduction in risk of cognitive decline and dementia in the Copenhagen City Heart Study (Schnohr et al., 2018).

The vicious cycle of decline is insidious: decreased movement leads to reduced capacity, which makes movement more difficult, causing further reduction in activity, which accelerates functional loss.

The good news? It's never too late to start. Previously sedentary individuals who begin exercise programs in their 70s and 80s show significant improvements in strength, mobility, and overall mortality risk. The human body truly operates on the principle: move it or lose it.

4. Movement Is Medicine (Not Rest): The Evolution of Injury Recovery

The traditional "RICE" (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) approach to injuries is being replaced by something that might sound counterintuitive: more movement. Modern sports medicine has evolved significantly, with mounting evidence suggesting that movement—not immobilization—is often the better approach for healing.

The Problem with Complete Rest

Complete immobilization following injury can actually impede the healing process in several key ways:

Reduced blood flow: Immobilization decreases circulation to the injured area, limiting the delivery of oxygen, nutrients, and healing factors.

Muscle atrophy: Studies show that just one week of immobilization can result in significant muscle atrophy—as much as 20-30% strength loss in some cases (Wall et al., 2013).

Collagen disorganization: Movement helps align collagen fibers along lines of stress during the healing process. Without this stress, collagen forms in a disorganized pattern, resulting in weaker tissue.

Joint stiffness: Immobilized joints rapidly develop adhesions and lose range of motion, which can become permanent if prolonged.

Cartilage degeneration: Joint cartilage requires movement to maintain health, as it has no direct blood supply and relies on movement for nutrition through synovial fluid.

The Evidence for Movement as Medicine

The shift toward "active recovery" is supported by robust research:

A 2010 meta-analysis in the Journal of Athletic Training concluded that early mobilization resulted in faster return to sports, reduced pain, and improved long-term outcomes compared to immobilization for ankle sprains (Bleakley et al., 2010).

For back pain—once treated with strict bed rest—a landmark study in The Lancet showed that patients who maintained normal activities recovered more quickly than those prescribed bed rest (Malmivaara et al., 1995).

Even for bone healing, controlled loading has been shown to enhance the process. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery published research demonstrating that appropriate mechanical stimulation actually accelerates fracture healing through increased callus formation (Goodship & Kenwright, 1985).

The New Paradigm: MOVE Instead of RICE

Many practitioners now advocate for variations of the "MOVE" approach:

Movement (rather than rest)

Options (individualized approaches)

Varied (different types of movement)

Ease (gradual progression)

That said, specific situations still warrant immobilization: unstable fractures before surgical fixation, complete tendon or ligament tears requiring surgical repair, and situations where movement would mechanically disrupt healing tissues.

So next time someone tells you to "stay off that ankle," you might want to ask if their medical knowledge has been updated since the Reagan administration.

5. The Twin Myths: Sweating Doesn't Equal Fat Loss & You Can't Spot Reduce Fat

Two persistent fitness myths often lead people astray: the belief that sweating means fat burning and that you can target fat loss from specific areas.

The Science Behind Sweating and Weight Loss

Sweating is simply your body's cooling mechanism. When your core temperature rises, sweat glands release water mixed with small amounts of electrolytes, urea, and lactate onto your skin. As this moisture evaporates, it creates a cooling effect.

The confusion arises because when you step on a scale after a sweaty workout, you might see a lower number—but that's temporary water loss, not fat loss.

Fat loss occurs through a metabolic process where stored triglycerides are broken down and used for energy, resulting in carbon dioxide and water as byproducts. This requires a caloric deficit—consuming fewer calories than you expend—not excessive sweating.

According to research published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, "the rate of fat oxidation during exercise is not affected by ambient temperature" (Gagnon et al., 2020). Intentionally increasing sweat through saunas, sweat suits, or hot yoga primarily increases water loss, not fat metabolism.

The Myth of Spot Reduction

Spot reduction—the belief that you can target fat loss from specific body parts through localized exercise—doesn't work physiologically. When your body mobilizes fat for energy:

Fat cells release fatty acids into the bloodstream throughout your body

These fatty acids enter circulation and become available to tissues throughout the body

Your body loses fat according to genetically predetermined patterns influenced by sex hormones, age, and individual factors

A classic study published in the Journal of Applied Physiology had subjects perform up to 5,000 sit-ups over the course of 27 days. Fat biopsies showed no significant difference in fat reduction between the abdominal region and other parts of the body (Katch et al., 1984).

What creates the appearance of "spot reduction" is actually two separate processes:

Overall fat loss through a sustainable caloric deficit

Targeted muscle building in specific areas through resistance training

So those "100 crunches a day for a six-pack" challenges? About as effective as trying to empty your swimming pool with a teaspoon while your neighbor is filling it with a hose.

6. "Toning" Doesn't Exist & Building Muscle Is Harder Than You Think

The fitness industry loves selling "toning" exercises that supposedly define muscles without building bulk. This language particularly targets women who want definition without "getting too muscular." But physiologically speaking, "toning" doesn't exist.

The Physiological Reality

What people call a "toned" appearance is actually the result of two simultaneous processes:

Muscle development - Having sufficient muscle mass to create visible shape

Fat reduction - Having low enough body fat percentage for that muscle to be visible

Muscles can only do three things: grow larger (hypertrophy), maintain their current size, or shrink (atrophy). There is no special "toning" response that makes muscles firmer without growth.

Sports scientist Brad Schoenfeld, Ph.D., explains in his research that: "The idea that one can 'tone' or 'shape' a muscle through specific exercise is not supported by scientific evidence. Muscle tone, in the physiological sense, refers to the constant tension in the muscle at rest, which is entirely different from the colloquial usage" (Schoenfeld, 2010).

The Reality of Building "Bulky" Muscle

The fear of becoming "too bulky" from lifting weights is equally unfounded. For women, hormonal differences (5-10% of men's testosterone levels) make significant muscle growth extraordinarily difficult. Research shows women engaging in consistent, heavy resistance training for 10 weeks typically gain only 1-2 pounds of muscle mass.

Even for men, building substantial muscle is far more challenging than most realize:

Natural bodybuilders typically gain only 2-3 pounds of actual muscle tissue per month in their first year of serious training—and that rate decreases dramatically with experience.

The 2% rule: Research suggests that most natural lifters can ultimately gain about 20-25 pounds of muscle beyond their starting point (roughly a 10% increase in total body weight for an average-sized man), and this takes years, not months.

Building muscle requires not just training stimulus but also consistent caloric surplus with adequate protein—a level of nutritional precision most casual gym-goers never achieve.

The "high rep, light weight" approach often recommended for "toning" is generally less effective than more challenging resistance training combined with appropriate nutrition. If building significant muscle were as easy as many fear, we'd have a lot more bodybuilders walking around—and a lot fewer gym memberships being sold.

7. Your Metabolism Adapts (For Better or Worse)

The concept of having a naturally "slow metabolism" is often used as an explanation for weight management challenges. However, the reality is much more complex and dynamic than this simplified view suggests.

What Metabolic Adaptation Actually Is

Metabolic adaptation refers to how your body adjusts its energy expenditure in response to various environmental and physiological factors. Rather than being a fixed, predetermined trait, your metabolism is responsive and adjustable.

Your total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) consists of several components:

Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) - The energy needed to keep your body functioning at rest (60-75% of total calories burned)

Thermic Effect of Food (TEF) - Energy used to digest and process food (10-15% of total calories)

Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) - Energy used for all movement outside of formal exercise (15-50% of total calories)

Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (EAT) - Energy used during intentional exercise (variable)

How Your Metabolism Adapts

When you significantly reduce calories, your body makes several adaptations:

Reduced BMR - Your resting metabolism slows beyond what would be expected from weight loss alone

Hormonal changes - Decreases in leptin, thyroid hormones, and testosterone; increases in ghrelin

Decreased NEAT - You unconsciously move less throughout the day

Improved metabolic efficiency - Your body becomes more efficient, requiring less energy for the same activities

A landmark study in the New England Journal of Medicine on "Biggest Loser" contestants found metabolic adaptation persisted for years after weight loss, with contestants burning 500+ fewer calories daily than would be predicted by their body composition (Fothergill et al., 2016).

During overfeeding, your metabolism also adapts when consistently overeating:

Increased NEAT - Spontaneous movement often increases

Higher TEF - Processing more food requires more energy

Increased BMR - Beyond what would be expected from weight gain alone

These adaptations explain why some people seem to "get away with" eating more without weight gain—their bodies compensate through increased activity and energy expenditure.

The Myth of the "Permanently Slow Metabolism"

While metabolic differences exist between individuals, research shows:

Most people with "slow metabolisms" actually have normal rates - Studies measuring metabolic rate using direct calorimetry find that most people claiming to have slow metabolisms actually have rates within normal ranges for their age, gender, and body composition.

Previous dieting history matters - Repeated cycles of significant weight loss and regain can create adaptations that persist.

Activity levels vary dramatically - NEAT can vary by up to 2,000 calories daily between individuals, far more than differences in resting metabolism.

Understanding metabolic adaptation can inform better approaches to health:

Gradual, moderate deficits are less likely to trigger severe metabolic adaptation than crash diets

Resistance training helps preserve or build metabolically active tissue

Protein intake becomes more important during weight loss to preserve muscle mass

Diet breaks can help reset some hormonal adaptations

Focusing on NEAT through daily movement may be more effective than increasing formal exercise

The notion that you're doomed by a "permanently slow metabolism" is largely a myth. While individual differences exist, your metabolism is remarkably responsive to your behaviors and environment.

8. All Diets Work Short-Term, Most Fail Long-Term

Virtually every popular diet works in the short term because they all create a caloric deficit through different mechanisms:

Low-carb/keto diets eliminate entire food categories, automatically reducing calories while increasing satiety through higher protein and fat

Intermittent fasting restricts eating windows, naturally reducing total food intake

Plant-based diets typically increase fiber and reduce calorie density

Mediterranean diets replace processed foods with whole foods

Commercial programs like Weight Watchers use point systems that essentially create calorie awareness

A 2014 meta-analysis in JAMA comparing different diets found minimal differences in weight loss outcomes between different named diet programs. The researchers concluded that "the differences are small and likely of little importance to those seeking weight loss." What mattered most was adherence, not which diet people followed (Johnston et al., 2014).

The Statistics on Diet Failure

According to research synthesis in "Fat Loss Forever" by Layne Norton, Ph.D.:

Only about 5% of people who lose significant weight manage to keep it off long-term.

The average dieter will make 4-5 major weight loss attempts per decade, with most regaining more weight than they initially lost.

This creates the destructive "yo-yo dieting" cycle that can worsen long-term metabolic health.

What Makes the 5% Successful?

Analysis of research on successful maintainers shows they typically:

Exercise 5+ hours per week, with emphasis on resistance training

Continue monitoring intake in some form (though not necessarily strict tracking)

Maintain higher protein intake even in maintenance

Have developed a healthy relationship with food rather than viewing it as "good" or "bad"

Use regular "reset" periods when weight starts creeping up rather than waiting for significant regain

Finding the perfect diet is like searching for a unicorn with a winning lottery ticket. The key isn't the specific program but creating sustainable lifestyle changes that account for biological challenges of maintenance. The best diet might not be the one that produces the fastest results, but the one you can actually stick with when the initial motivation fades—and that's usually the one that least feels like a diet at all.

9. Health Transformation Requires Identity Shift

Lasting health improvement often requires more than just a new diet or exercise plan—it demands a fundamental shift in how we see ourselves. This identity-based approach is supported by both psychological research and physiological science.

Fixed vs. Growth Mindset in Health

Our approach to health challenges is profoundly influenced by our mindset:

Fixed Mindset: Views health capabilities as static—"I'm just not a workout person" or "Everyone in my family is overweight."

Growth Mindset: Sees health as developable—"I'm building my endurance" or "I'm learning to enjoy nutritious foods."

Research by psychologist Carol Dweck has demonstrated that mindset powerfully influences achievement across domains. In health specifically, studies show that individuals with a growth mindset are more likely to persist through challenges, recover better from setbacks, and view effort as a path to improvement (Dweck, 2006).

The Physiological Basis for Identity Shifts

Our bodies possess remarkable adaptability that supports the concept of health identity transformation:

Cellular Renewal: The majority of cells in the human body are replaced over time. Red blood cells last about 120 days, skin cells 2-3 weeks, and even portions of the skeleton are continuously remodeled.

Neuroplasticity: The brain remains changeable throughout life. Research in neuroscience has conclusively shown that new neural pathways form in response to learning, environment, and behavior changes.

Epigenetic Adaptations: While your genetic code remains stable, how those genes are expressed can change significantly. Lifestyle factors like exercise, diet, stress management, and sleep can alter gene expression patterns.

Microbiome Transformation: The gut microbiome can undergo near-complete transformation within 2-4 weeks of significant dietary changes. These microorganisms influence everything from weight management to mental health.

Why We Cling to Unhealthy Identities

Despite the body's adaptability, people often resist health identity changes for several reasons:

Identity Defense: We're psychologically wired to protect our self-concept. Changing identity triggers uncertainty and vulnerability.

Comfort in Familiarity: Even harmful identities provide psychological comfort and excuse-making frameworks.

Social Reinforcement: Our social circles often reinforce our existing identities. Changing can threaten relationships and trigger resistance from others.

Fear of Failure: Attempting change creates the possibility of failure. Many prefer the certainty of an unchanging but problematic identity to the uncertainty of transformation.

All-or-Nothing Thinking: Many see identity as binary—either you're athletic or you're not. This overlooks the gradual nature of identity development.

The Process of Health Identity Transformation

Research suggests several evidence-based approaches to health identity shifts:

Identity Forecasting: Visualizing and describing your future health identity in specific terms activates neural pathways that make behavioral change more likely.

Tiny Identity Shifts: Major identity transformations begin with small actions aligned with the new identity. Each small "identity-congruent" choice strengthens neural pathways supporting the new self-concept.

Community Reinforcement: Surrounding yourself with people who embody your desired health identity accelerates transformation through both social learning and identity reinforcement.

Identity-Based Habits: Framing health behaviors as expressions of identity ("This is what a healthy person does") rather than isolated actions creates more sustainable change than goal-focused approaches.

Self-Compassion During Transitions: Research shows that self-compassion—not self-criticism—facilitates behavior change by reducing the shame and avoidance that follow inevitable setbacks (Neff & Germer, 2013).

The most powerful health question isn't "What should I do?" but rather "Who do I want to become?" After all, someone who identifies as a runner doesn't debate whether to go running—they just lace up their shoes and head out the door, even when they don't particularly feel like it. That's the power of identity.

10. Sustainable Health Changes Start Small But Compound Over Time

The most successful health transformations rarely begin with dramatic overhauls. Instead, they start with small, consistent changes that compound over time—much like interest in a financial investment.

The science of habit formation shows that consistency matters more than intensity, especially in the beginning. Each small action reinforces neural pathways that make the behavior increasingly automatic, requiring less conscious effort over time.

The Science of Tiny Habits

Stanford behavior scientist BJ Fogg's research demonstrates that tiny habits—actions so small they seem almost trivial—can be the foundation for significant behavior change when:

They're tied to existing routines (habit stacking)

They're immediately followed by a celebration (reinforcement)

They gradually expand in scope as they become automatic (Fogg, 2019)

This approach aligns with how our bodies adapt physiologically:

Cardiovascular fitness improves through consistent, progressive overload

Muscle development occurs through regular stimulus, recovery, and slight progression

Metabolic health improves through consistent rather than extreme dietary patterns

Mobility increases through regular movement practice rather than occasional stretching sessions

The compound effect of small changes is powerful but often invisible in the short term—much like the parable of the Chinese bamboo tree, which shows little growth for four years before shooting up 80 feet in the fifth year. Those initial years aren't failures; they're establishing the root system needed for explosive growth.

Practical Applications

Implementing the principle of small changes includes:

Adding one vegetable serving before focusing on removing processed foods

Walking 10 minutes daily before progressing to more intense exercise

Improving sleep habits before overhauling your diet

Practicing basic movement patterns before beginning complex training programs

The most sustainable approach to health improvement isn't the most exciting or marketable—it's simply doing slightly better than yesterday, consistently, over a long period. The gap between where you are and where you want to be is filled not by dramatic leaps but by small steps taken with remarkable consistency.

To your continued progress,

About the Author

Dr. Matt Eichler bridges two crucial worlds in fitness: as both a practicing chiropractor and a fitness coach, he sees firsthand how movement quality impacts everyday life. After helping thousands of patients overcome pain and injury, he noticed a clear pattern - most gym injuries weren't random accidents, but the result of predictable, preventable factors.

This unique perspective shaped his training philosophy: that sustainable fitness isn't about avoiding movement, but about moving intelligently. Through his practice and Element X Personal Transformations (EXPT), Dr. Matt helps people build stronger, more resilient bodies by combining clinical expertise with practical training wisdom.

His approach focuses on meeting you where you are, whether you're dealing with old injuries, just starting your fitness journey, or looking to take your training to the next level - all while keeping the long game in mind. Because as he often tells his clients, "The goal isn't to never experience discomfort - it's to build a body that can handle whatever life throws at it."

When he's not treating patients or coaching clients, Dr. Matt continues expanding his knowledge in pain science, movement mechanics, and performance training, bringing the latest evidence-based practices to his community.

References

Biswas, A., Oh, P. I., Faulkner, G. E., Bajaj, R. R., Silver, M. A., Mitchell, M. S., & Alter, D. A. (2015). Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 162(2), 123-132.

Bleakley, C. M., McDonough, S. M., & MacAuley, D. C. (2010). Some conservative strategies are effective when added to controlled mobilisation with external support after acute ankle sprain: a systematic review. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 56(1), 7-21.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Chronic Diseases in America. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/infographic/chronic-diseases.htm

Christensen, K., Doblhammer, G., Rau, R., & Vaupel, J. W. (2006). Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. The Lancet, 368(9547), 1174-1183.

Convertino, V. A. (1997). Cardiovascular consequences of bed rest: effect on maximal oxygen uptake. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 29(2), 191-196.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

English, K. L., & Paddon-Jones, D. (2010). Protecting muscle mass and function in older adults during bed rest. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 13(1), 34.

Fogg, B. J. (2019). Tiny habits: The small changes that change everything. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Fothergill, E., Guo, J., Howard, L., Kerns, J. C., Knuth, N. D., Brychta, R., ... & Hall, K. D. (2016). Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after "The Biggest Loser" competition. Obesity, 24(8), 1612-1619.

Gagnon, D. D., Perrier, L., Dorman, S. C., Oddson, B., Larivière, C., & Serresse, O. (2020). Ambient temperature does not influence substrate oxidation rates during submaximal exercise in men. European Journal of Sport Science, 20(9), 1160-1167.

Goodship, A. E., & Kenwright, J. (1985). The influence of induced micromovement upon the healing of experimental tibial fractures. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 67(4), 650-655.

Johnston, B. C., Kanters, S., Bandayrel, K., Wu, P., Naji, F., Siemieniuk, R. A., ... & Mills, E. J. (2014). Comparison of weight loss among named diet programs in overweight and obese adults: a meta-analysis. JAMA, 312(9), 923-933.

Katch, F. I., Clarkson, P. M., Kroll, W., McBride, T., & Wilcox, A. (1984). Effects of sit up exercise training on adipose cell size and adiposity. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 55(3), 242-247.

Khera, A. V., Emdin, C. A., Drake, I., Natarajan, P., Bick, A. G., Cook, N. R., ... & Kathiresan, S. (2016). Genetic risk, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and coronary disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(24), 2349-2358.

Knowler, W. C., Barrett-Connor, E., Fowler, S. E., Hamman, R. F., Lachin, J. M., Walker, E. A., & Nathan, D. M. (2002). Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. New England Journal of Medicine, 346(6), 393-403.

Krogh-Madsen, R., Thyfault, J. P., Broholm, C., Mortensen, O. H., Olsen, R. H., Mounier, R., ... & Pedersen, B. K. (2010). A 2-wk reduction of ambulatory activity attenuates peripheral insulin sensitivity. Journal of Applied Physiology, 108(5), 1034-1040.

Malmivaara, A., Häkkinen, U., Aro, T., Heinrichs, M. L., Koskenniemi, L., Kuosma, E., ... & Vaaranen, V. (1995). The treatment of acute low back pain—bed rest, exercises, or ordinary activity? New England Journal of Medicine, 332(6), 351-355.

Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self‐compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 28-44.

Schnohr, P., O'Keefe, J. H., Lavie, C. J., Holtermann, A., Lange, P., Jensen, G. B., & Marott, J. L. (2018). Various leisure-time physical activities associated with widely divergent life expectancies: the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 93(12), 1775-1785.

Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857-2872.

Schroeder, S. A. (2007). We can do better—improving the health of the American people. New England Journal of Medicine, 357(12), 1221-1228.

Wall, B. T., Dirks, M. L., Snijders, T., Senden, J. M., Dolmans, J., & Van Loon, L. J. (2013). Substantial skeletal muscle loss occurs during only 5 days of disuse. Acta Physiologica, 210(3), 600-611.

World Health Organization. (2020). Physical inactivity: A global public health problem. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity

Yusuf, S., Hawken, S., Ôunpuu, S., Dans, T., Avezum, A., Lanas, F., ... & INTERHEART Study Investigators. (2004). Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. The Lancet, 364(9438), 937-952.

Health Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for educational and informational purposes only. It is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any health conditions, nor should it be considered a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult with your doctor or qualified healthcare provider before starting any new health program, making changes to your diet, taking supplements, or if you have questions about your medical condition. Your health decisions should be based on discussions with your healthcare team, not on the content you read online.

Comments